In 1488, Philipp wrote to Archduke Sigismund (1427–1496) to thank him for a promised harness. Philipp asked for a simple, functional harness and sent a doublet and hose so the armourer could gauge his size.

Iron Men – Mode in Stahl

loading

Armour is made of iron, quite frequently even of steel. But despite the hard material it is surprisingly flexible.

One can walk, run and jump in a harness. If necessary, one can even do summersaults.

A harness comprises numerous individual pieces – the most important are helmet, gorget, breast- and backplate, rere- and vambraces, greaves, and cuisses.

A gauntlet can comprise up to seventy metal pieces, a harness up to 200.

Harnesses were worn by men.

The most obvious symbol of this is the codpiece. Part of the (textile) garments worn by men, it was also incorporated into some harnesses.

A harness is a piece of clothing made of steel.

It was fashionable, and, like all clothes, it reflected contemporary taste.

Armourers even produced harnesses with armoured skirts and puffed sleeves.

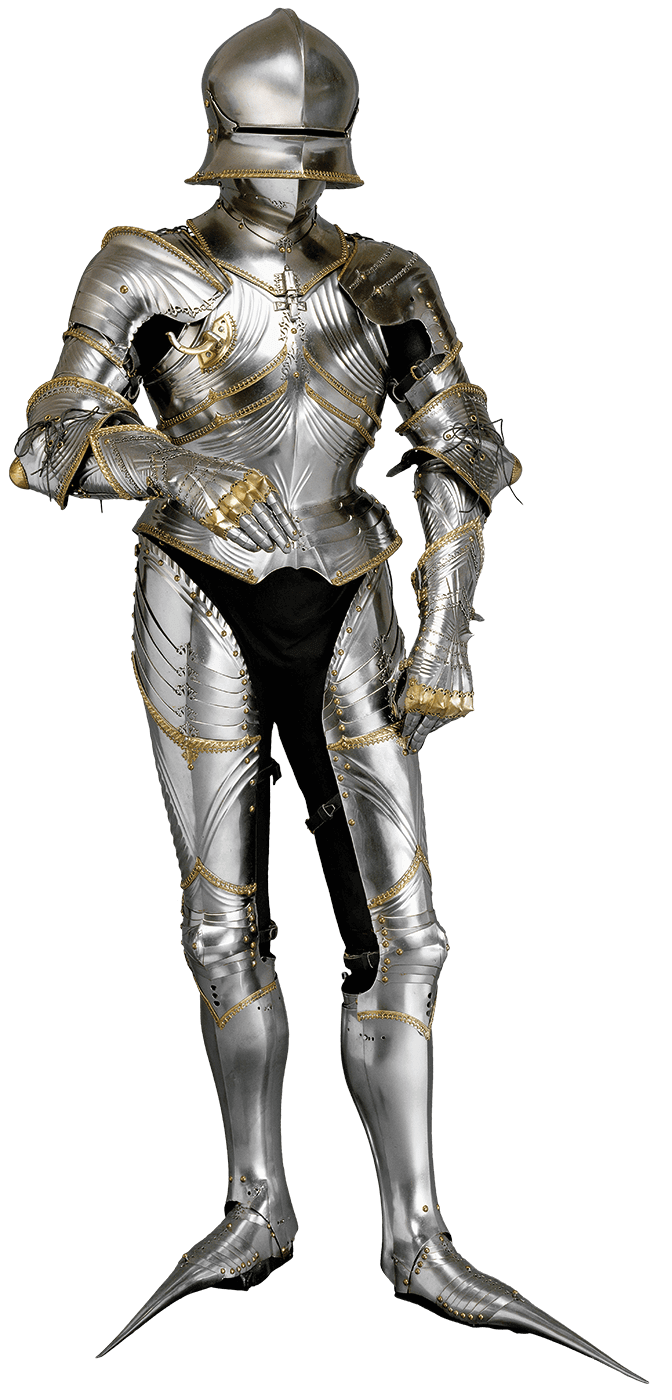

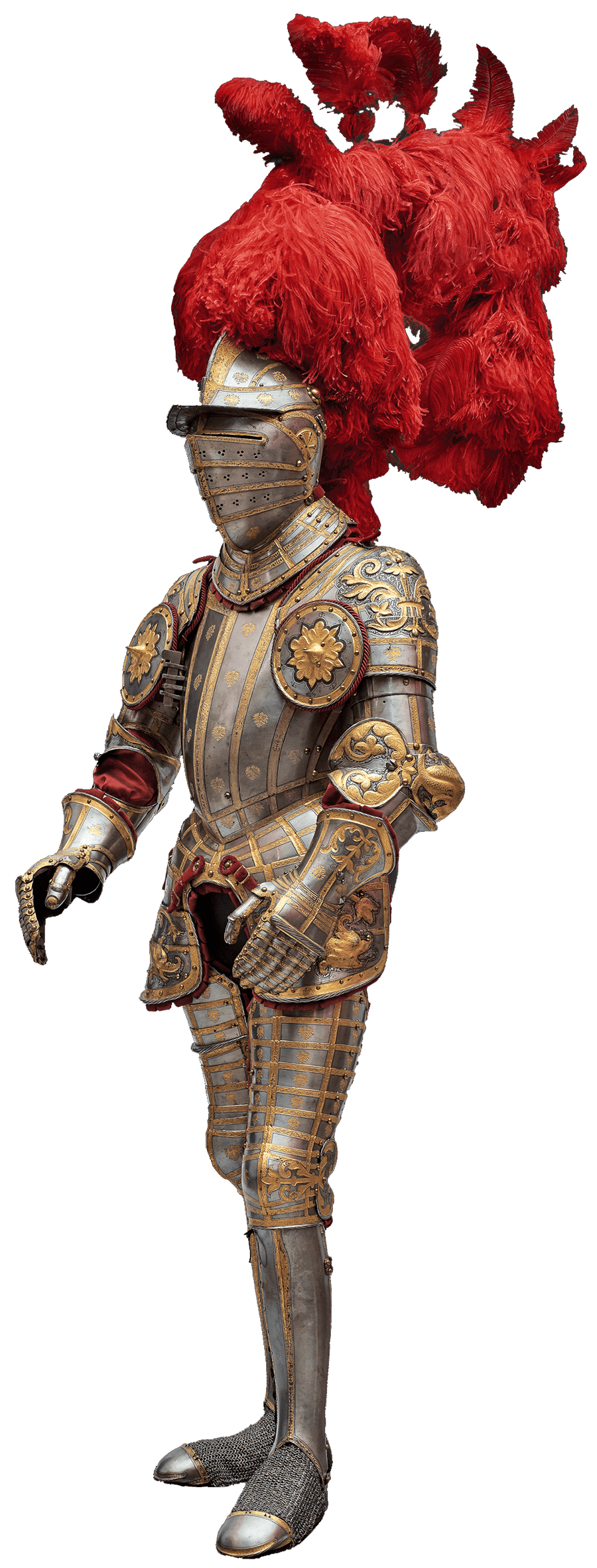

This is one of the most exceptional Renaissance harnesses, a highpoint of German armour making.

It belonged to Wilhelm von Rogendorf (1481–1541), who served Emperor Charles V as a diplomat and general.

But Rogendorf did not wear it in battle. Cutting a fine figure, he donned it for pageants and festivities.

Five centuries ago, the harness played a seminal role in European culture and warfare. But this archetypal piece of steel protective clothing continues to impact our language:

someone has to earn his spurs. I break a lance for someone. You host a sports tournament.

A harness played different roles in the lives of men – and of some women – it was fashion and fancy dress, and everything from a boy’s armour to his funeral helm.

Boys’ armour

In the Renaissance, fully-functioning miniature harnesses were commissioned for the sons of princes and rulers.

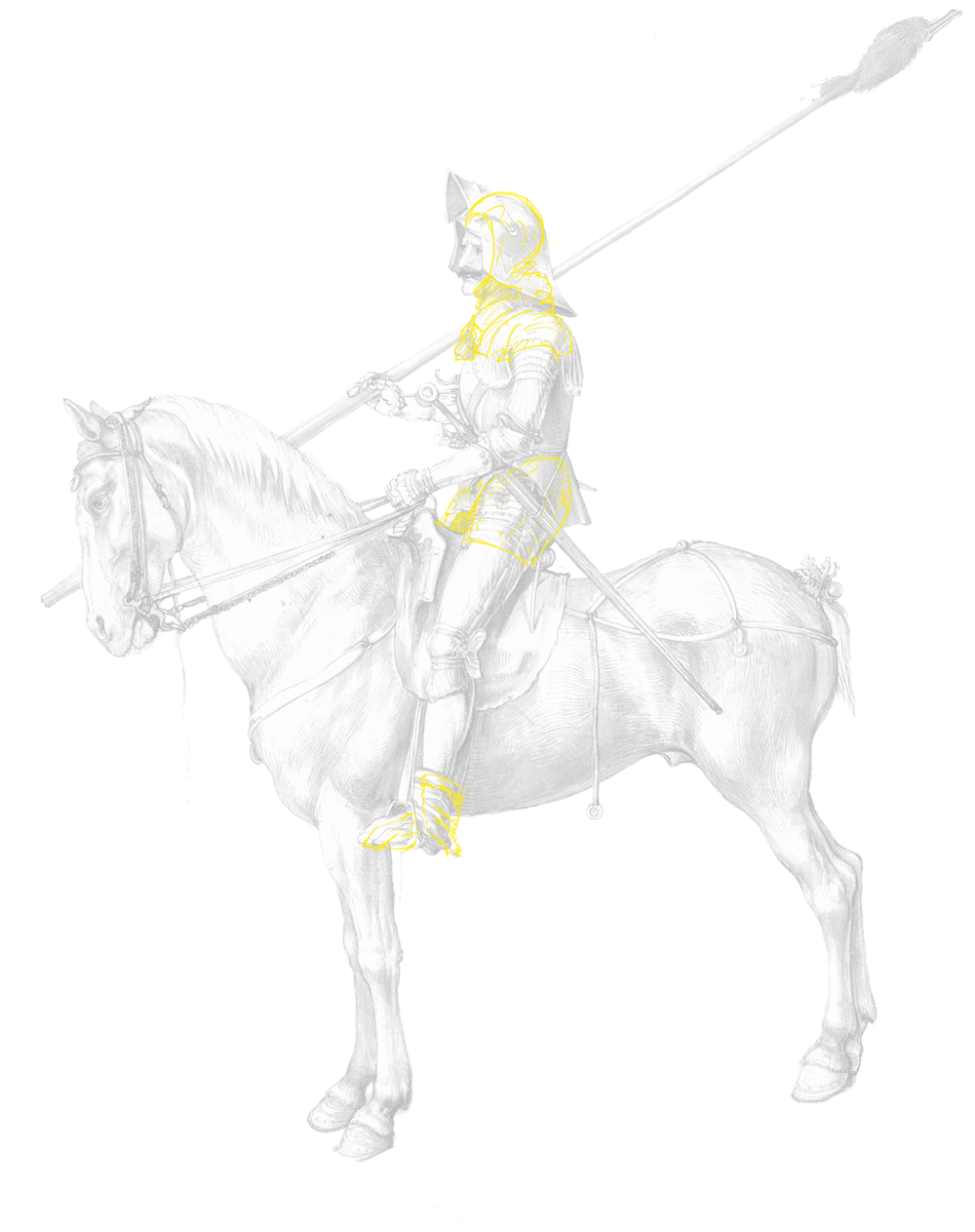

Boy’s harness for Philip the Handsome, King of Castile (1478–1506)

Hans Prunner (ment. 1482–1499)

Innsbruck, 1488/89

Steel, embossed; brass; leather

H 121 cm; 5.2 kg

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Imperial Armoury, inv. A 9

Boys’ armour was not intended to be worn on the battlefield or in the lists.

Instead, they reflected the dynastic and political stability of the ruling family. They functioned as visual proof of continuity.

We know of many young sons who proudly showed off their new armours. Others, like ten-year-old Philipp the Handsome (1478–1506), the son of Emperor Maximilian I (1459–1519), eagerly awaited the delivery of a new harness.

Boys’ harnesses were luxury objects. They cost as much as armour for a grown man but their young wearers outgrew them quickly.

Attributed to Alonso Sánchez Coello (1531/32–1588)

c.1562

Canvas

149.7 × 101.7 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery, inv. 3175

These harnesses were made-to-measure. They could not simply be handed down to a younger brother, for example. This is why so few boys’ armours have survived.

Some of these harnesses could be ‘let out’ when their young owner grew. For instance, additional holes in the straps made it possible to let out iron plates.

In a letter written in 1516, Emperor Maximilian I mentions special screws that allowed a boy’s harness to be ‘used for three years’.

Grown-up men grow too

Not only boys, grown me too could grow – but mainly in width not in height. If a knight put on weight, he generally had no choice but to order a new harness.

The harnesses produced for King Henry VIII of England (1491–1547) bear eloquent witness to this. Armour made for the young Tudor suggests a lithe and fit body. Those he commissioned later in life were made for a heavily overweight man.

As the Livre de Chevalerie (‘Book of Chivalry’, c.1380) reminds us,

‘one has seen many of those thus constricted who have to take off their armour in a great hurry, for they could no longer bear to wear their equipment’

Innsbruck (Mühlau?), c.1505

Cast bronze with traces of old paint

H 11 cm, W 6.5 cm, D 12 cm (each)

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Kunstkammer (Imperial Armoury), invs. KK 81, KK 92

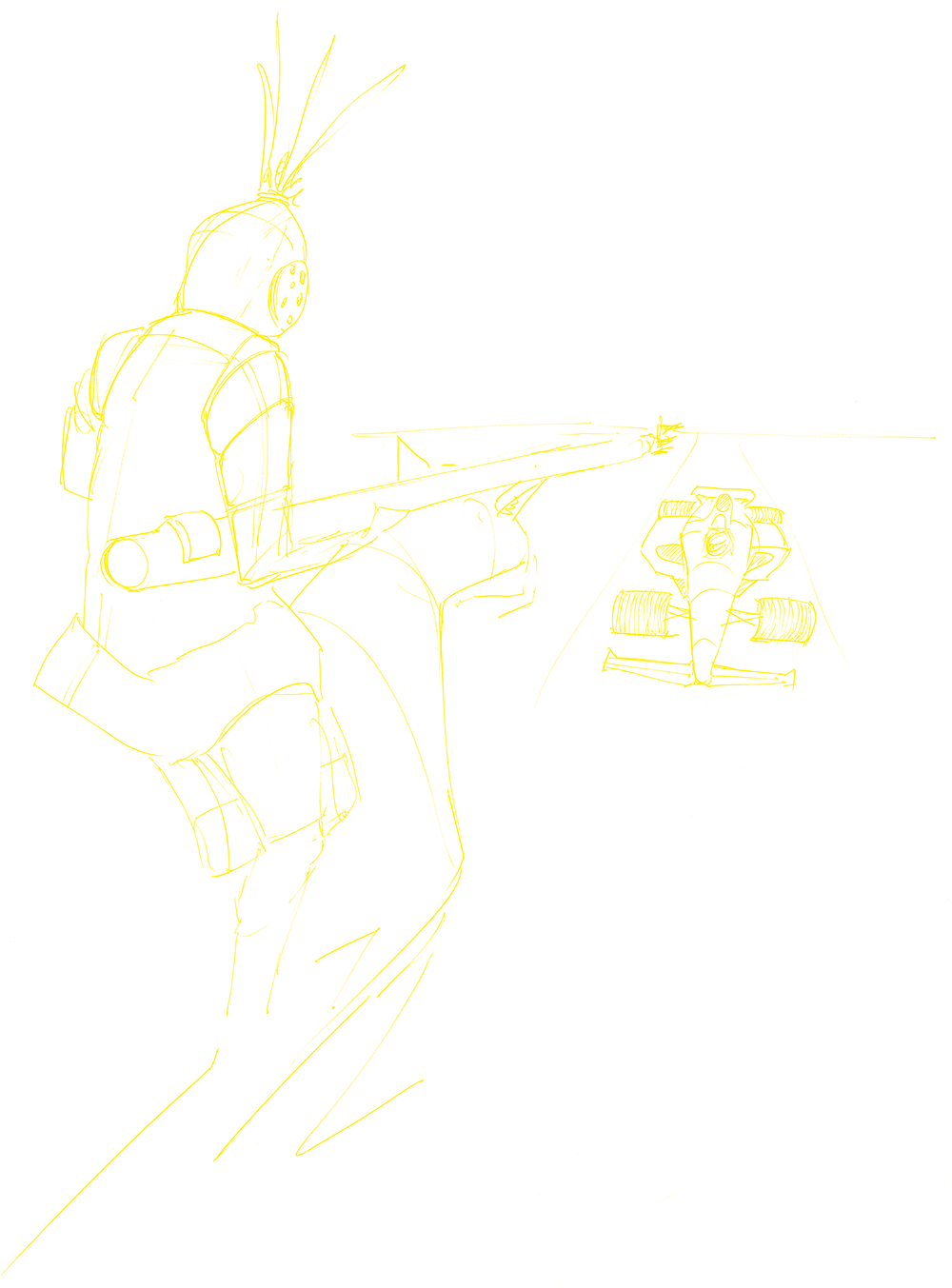

These figurines are the only extant complete set of jousting toys from the late Middle Ages. Only the lances are modern replacements.

Ribbons or a piece of string could be threaded into their bases, allowing the players to pull the knights towards each other. If the lance of one hit his opponent, the latter was unhorsed.

The young players were clearly familiar with all the rules and tricks of the then-popular sport of jousting.

Tournaments – competition, politics and show

Late-mediaeval tournaments may seem strange and brutal to us. But we too love risky sports – only the type of sport has changed.

Like modern sports equipment, jousting armour was optimized for the particular risks of these competitions and offered their wearers excellent protection.

Tournaments evolved in the High Middle Ages, probably at the end of the eleventh century. Initially, they were a form of military training with the then-novel lance.

‘Tournament’ comes from the Latin tornare (to turn), which refers to the frequent and fast turns executed during these training sessions.

These exercises proved the ideal setting for knights to display their skills. They quickly evolved into elaborately staged competitions and exhibition fights. Tournaments also included banquets, dances and pageants.

Tournaments were often held in connection with important political events such as Imperial Diets, coronations or weddings. They offered a chance to network and for diplomatic exchanges, but they also functioned as a marriage market.

Matthäus Frauenpreis the Elder (c.1505–1549), Jörg Sorg the Younger (c.1522–1603)

Augsburg, 1549/50

Steel, embossed, etched, fire-gilt; brass, fire-gilt; leather (partly modern), silk velvet (partly modern)

H 173.5 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Imperial Armoury, inv. A 610

Jörg Seusenhofer (c.1510–1580)

Innsbruck, 1547

Iron, wrought, embossed, etched, fire-gilt, blackened; brass, fire-gilt, engraved; leather; silk velvet, silk, wool

H 168.5 cm, W 72.5 cm, D 47 cm; 19.5 kg

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Imperial Armoury, inv. A 638

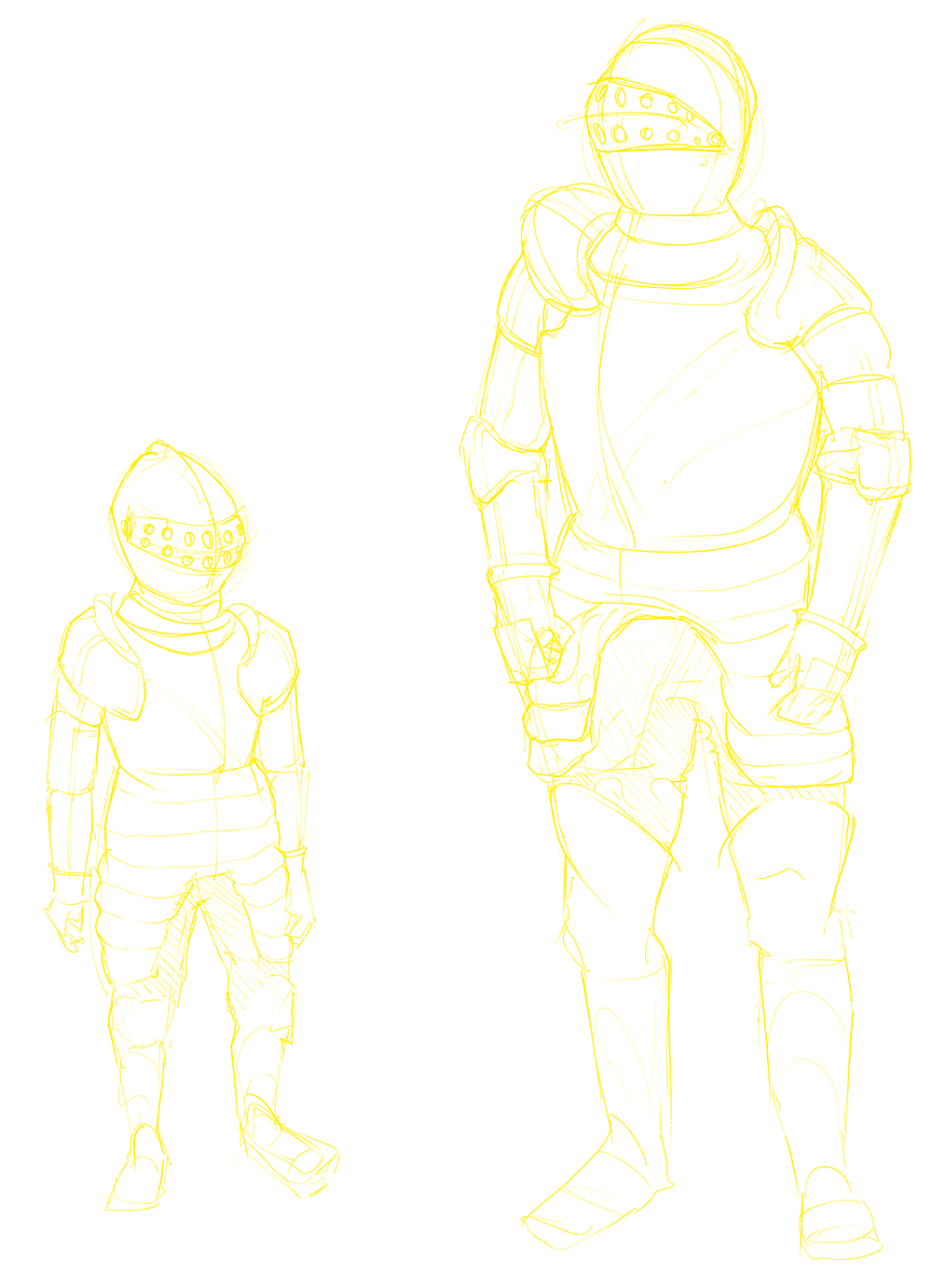

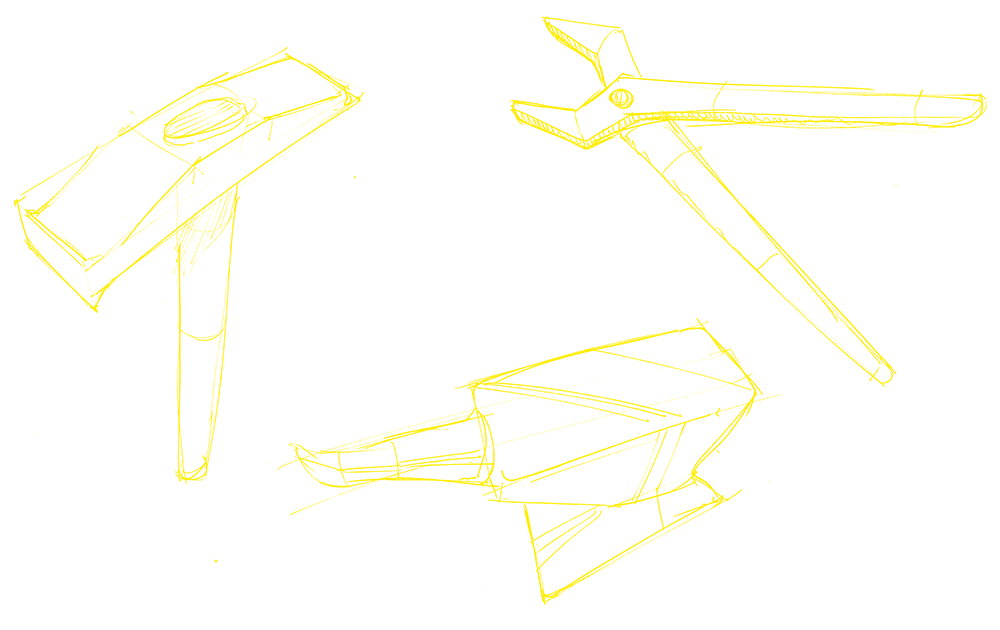

There were many different forms of tournament. A special harness was developed for each of them. They differ greatly in shape and construction.

On the left is armour for a joust of peace, with the tilt. Here, the mounted jousters are separated by the tilt, a wooden barrier. They aimed their lances at their opponent’s shield, which was screwed onto his harness.

On the right is a harness for a foot tournament. Participants faced off on foot armed with swords or maces. Their waists and thighs were protected by a wide armoured skirt.

Chivalrous tournaments were competitions in which only men could participate. But ladies too played an important role at these festivities.

During the so-called ‘inspection of the helmets’, the ladies of the court verified the participants’ pedigrees. In this they were joined by a herald, a royal officer of arms versed in heraldry. If they discovered an interloper, his helmet could easily land in the gutter.

Before the competition commenced, ladies often presented one of the jousters with a so-called faveur. These were small signs of their favour such as a handkerchief, a small crown, or a shawl. The knight attached it to his helmet or lance and defended it against all attempts by his opponents to take it off him.

At the end of the tournament, the most high-ranking lady of the court presented the prize to the winner. This could be a piece of jewellery, a fine horse, or a precious sword.

The harness – a form of protective clothing

A steel harness was a form of protective clothing worn on the battlefield and in the lists. It is made of iron and is therefore, not surprisingly, heavier than textile garments.

But a harness is also lighter and more flexible than many probably imagine.

The idea that a harness is incredibly heavy and greatly restricts the wearer’s mobility is modern nonsense. A harness was designed to move in and with it.

David Teniers the Younger (1610–1690)

c.1652

Canvas

203.5 × 136 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery, inv. 3504

Steel armour was a European invention and was mainly worn in Europe. It is primarily a phenomenon of the late Middle Ages and especially the Renaissance.

A harness was optimized for the conditions of fighting with lances and swords. Initially it also offered protection against infantry arms such as pikes, arrows and crossbows.

One of the most popular questions regarding armour is its weight. How heavy is it, and how easy is it to move in it?

A harness is not light, but it is lighter and more flexible than it appears. A field harness normally weighs around 20–30 kg (c.40–60 lbs). This is similar to the equipment carried by many modern firemen.

But the weight was distributed evenly over the entire body. Unlike a full backpack, which is carried by the shoulders alone.

Only some special types of armour are heavier: jousting armour could weigh up to 35 kg (c.70 lbs). Later, armour of proof, designed to withstand powerful firearms, could even weigh as much as 50 kg (100 lbs).

A harness comprises countless individual pieces, often as many as 200. These pieces were carefully but not rigidly joined together. It was therefore not a problem to walk, run or jump in a harness, or to climb stairs, lie on the ground and get up again.

Augsburg, c.1485,

weight: 21.25 kg.

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna,

Imperial Armoury, inv. A 62

If necessary, one can even do summersaults in a harness. With a bit of training a man could even ‘leap fully armed onto his horse’, something we know Jean II Le Meingre called Boucicault (1366–1421) did.

But this does not mean that a harness is as comfortable and easy to wear as textile clothes. ‘Any man of understanding will see that an unarmed man moves more swiftly than an armed man’, wrote Gutierre Diaz de Gamez in his book El Victorial (c.1436–1448).

To get used to wearing a harness, Olivier de la Marche advised aspiring knights in his Le Chevalier deliberé (1483) to ‘put on a mail shirt and add some lead to their shoes.’

Archduke Albert VII

1604

Paper

340 × 240 mm (closed)

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Library, sig. 13.565

Wearing a harness and participating in chivalrous fights were male domains.

But we know of some women in the Renaissance who fought in battles. Some of them were probably motivated by poverty, others by a love of adventure.

On 7 January 1602, the Spanish launched an attack on the Dutch fortress of Ostend. After the battle was over, they were surprised to discover ‘a Spanish woman dressed in men’s clothes’ among the dead.

The report on the siege records that the woman had ‘joined in the attack’.

Desiderius Helmschmid (1513–1579), Ulrich Holzmann (ment. 1534–1562)

Augsburg, 1544

Steel, embossed, etched, fire-gilt, blackened; leather; brass, fire-gilt

H 167 cm; 17.3 kg

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Imperial Armoury, inv. A 547

Juan Pantoja de la Cruz (1563–1608)

c.1601/02

Canvas

176 × 116 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery, inv. 9490

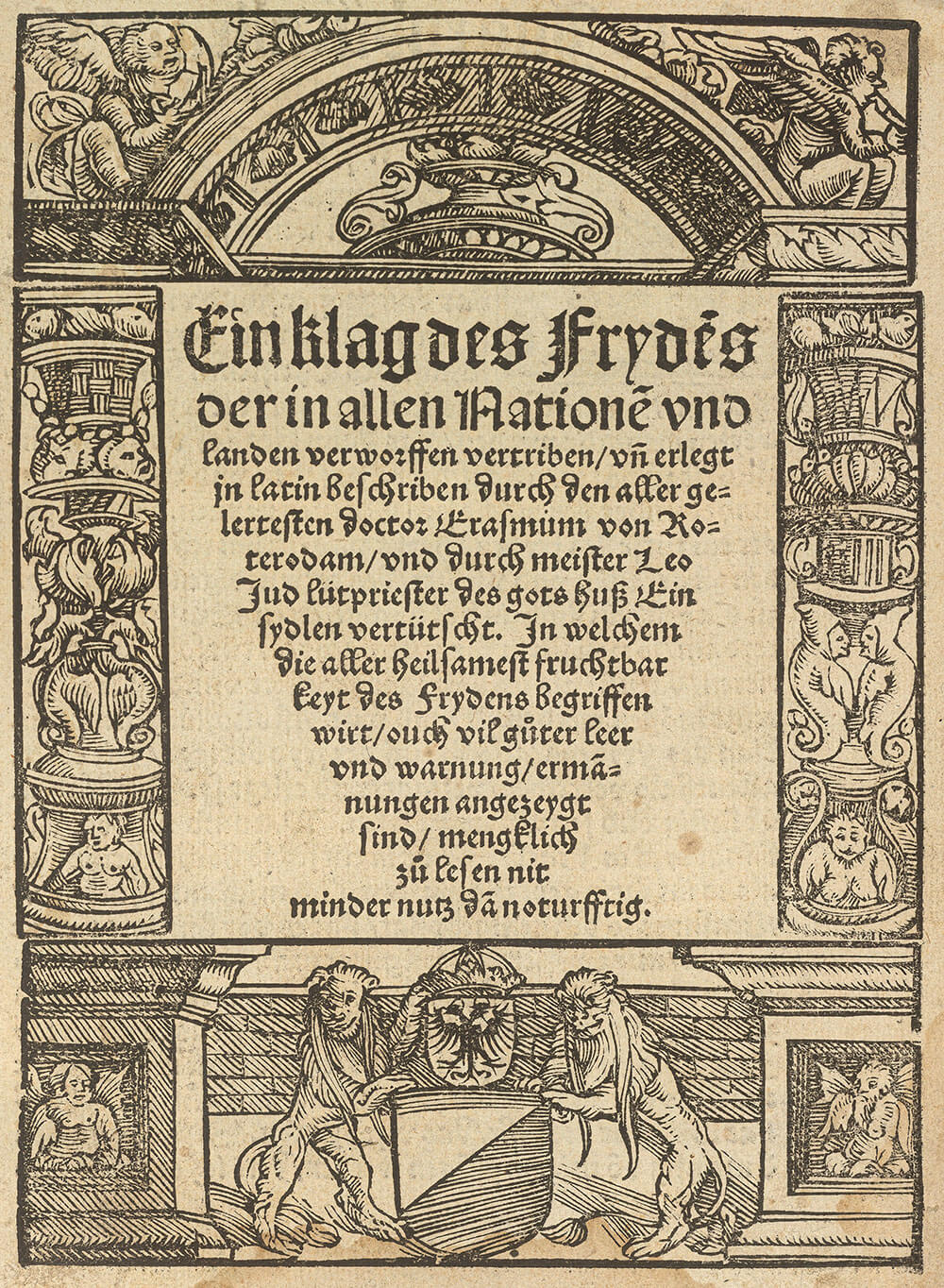

QUERELA PACIS – THE COMPLAINT OF PEACE, 1517

In 1517, the young Emperor Charles V commissioned the celebrated Netherlandish humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam to compose a programmatic text about the importance of peace. It was intended for the international peace congress planned but never held at Cambrai in 1517.

Erasmus of Rotterdam

First German translation of the Querela Pacis

Printer: Christophorus Froschouer, Zurich 1521

Austrian National Library, Picture Archives and Graphics, sig. 261884-B

© ÖNB/Wien, 261884-B

‘But I blush to record, upon how infamously frivolous causes the world has been roused to arms by Christian kings.’

‘Kings! to you I make my first appeal. On your nod, such is the constitution of human affairs, the happiness of mortals is made to depend … hear the voice of your Sovereign Lord, commanding you, upon your duty, to seek peace and abolish war. Be persuaded that the world, wearied with its long-continued calamities, demands this.’

Quoted from: Desiderius Erasmus, The Complaint of Peace, Open Court, 1521

Beyond the grave

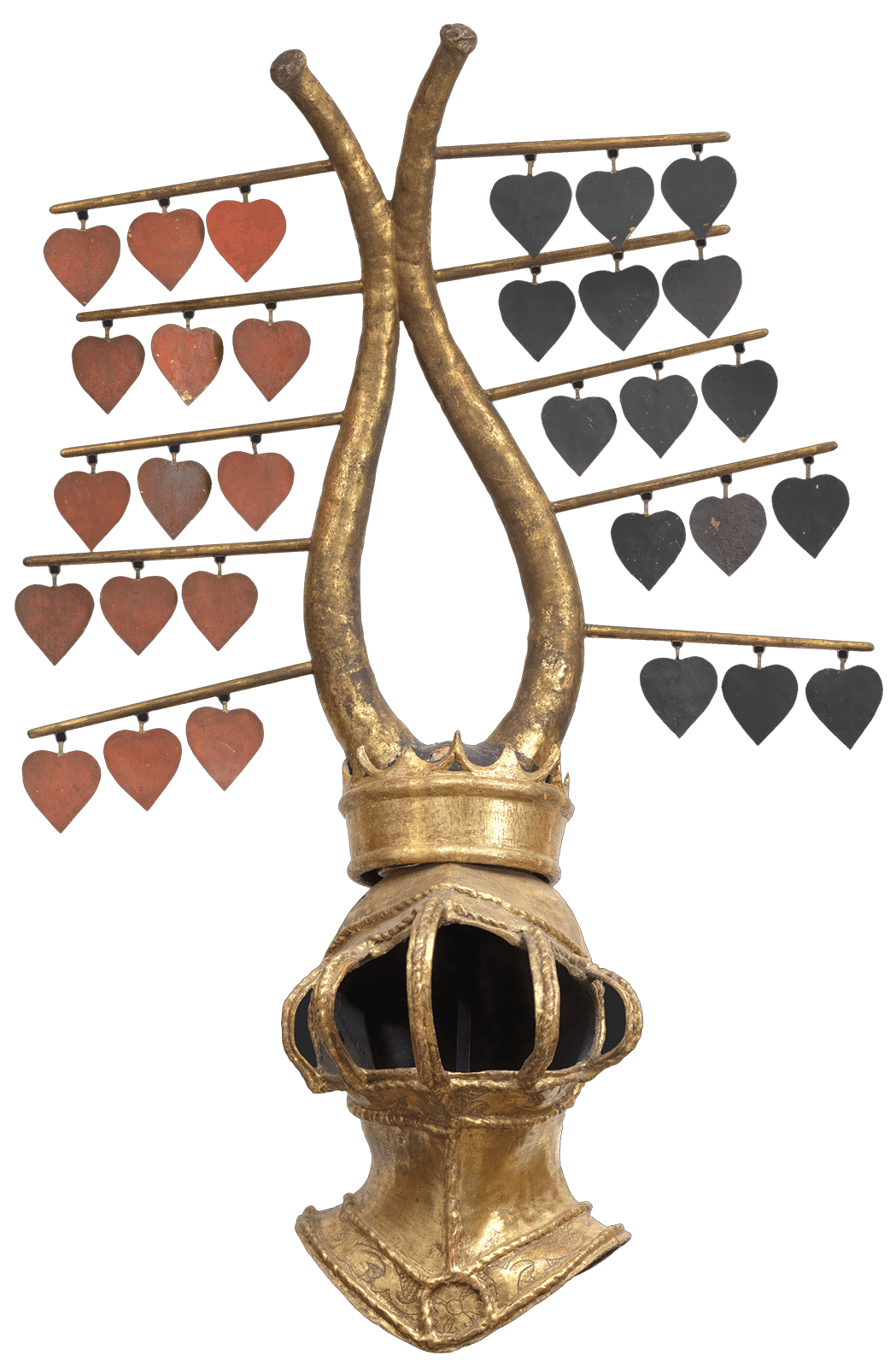

Since the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, helmets have functioned as emblems of chivalry.

Helmets symbolised their wearer’s political and military authority. They were treasured personal belongings.

From this evolved the custom of displaying helmets – sometimes even full armours – to commemorate a deceased knight in the church where he was buried.

These helmets are called ‘funeral helms’.

Innsbruck, 1595

Paper; brown pen, watercolour; opaque paint

Page 1: 182 × 575 mm; page 8: 179 × 465 mm; page 9: 200 × 395 cm; page 10: 203 × 396 mm

Vienna, Albertina, inv. 47483/9

Helmets were included among the insignia and signs of rank borne in the funerary procession of a prince.

There are two types of funeral helms. One option was to use real steel helmets, many of which came from the deceased’s estate. Or such helmets were especially produced for a funeral, in which case they were made of painted wood and would have been useless on a battlefield.

Most funeral helms were decorated with a crest. The latter could be read as heraldic or political symbols. But they also functioned as fantastic decorations.

Austrian, 1463

Wood; leather, painted, gilt

H 76 cm, W 75 cm, D 46 cm

Wien Museum, inv. 126.166

Austrian, 1493

Wood; metal; leather, painted, gilt

H 109 cm, W 73.5 cm, D 36 cm

Wien Museum, inv. 126.184

In the church, the funeral helm was initially placed on the tomb of the deceased knight. Later, it was usually placed high up above the tomb on the wall of the church.

A funeral helm symbolised that the deceased had returned all temporal powers to God, as well as his martial achievements and his chivalrous life.

Most of the extant funeral helms are in churches in England. One of them is the funeral helm of Edward the Black Prince (1330-1376), which is still displayed at Canterbury Cathedral.

Great helm surmounted by a crest made for Albert von Prankh (?)

Austrian, c.1330

Iron, wrought; crest: leather; linen, chalk ground, leaf gilded, leaf silvered; varnish

H 72.3 cm W 4.2 cm, D 29 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Imperial Armoury, inv. B 74

The great helmet of Albert von Prankh (fig.) was originally installed at Seckau Abbey in Styria. It hung high up on the wall in the southern side aisle of the church, below two funeral shields of the noble Prankh family.

From iron ore to the complete harness

Numerous people were involved in the production of a harness, each one a specialist in his field.

Erzberg- Eisenerzlagerstätte, Abbauetage Antoni,

Östliche Grauwackenzone

Miners won the ore, ironworkers turned it into iron in a bloomery.

Armourers produced pieces of armour. Painters, graphic artists and goldsmiths embellished them.

Tailors, tanners, and buckle-makers made the textile and leather fittings. Carpenters built the boxes in which the harnesses were dispatched to their new owners.

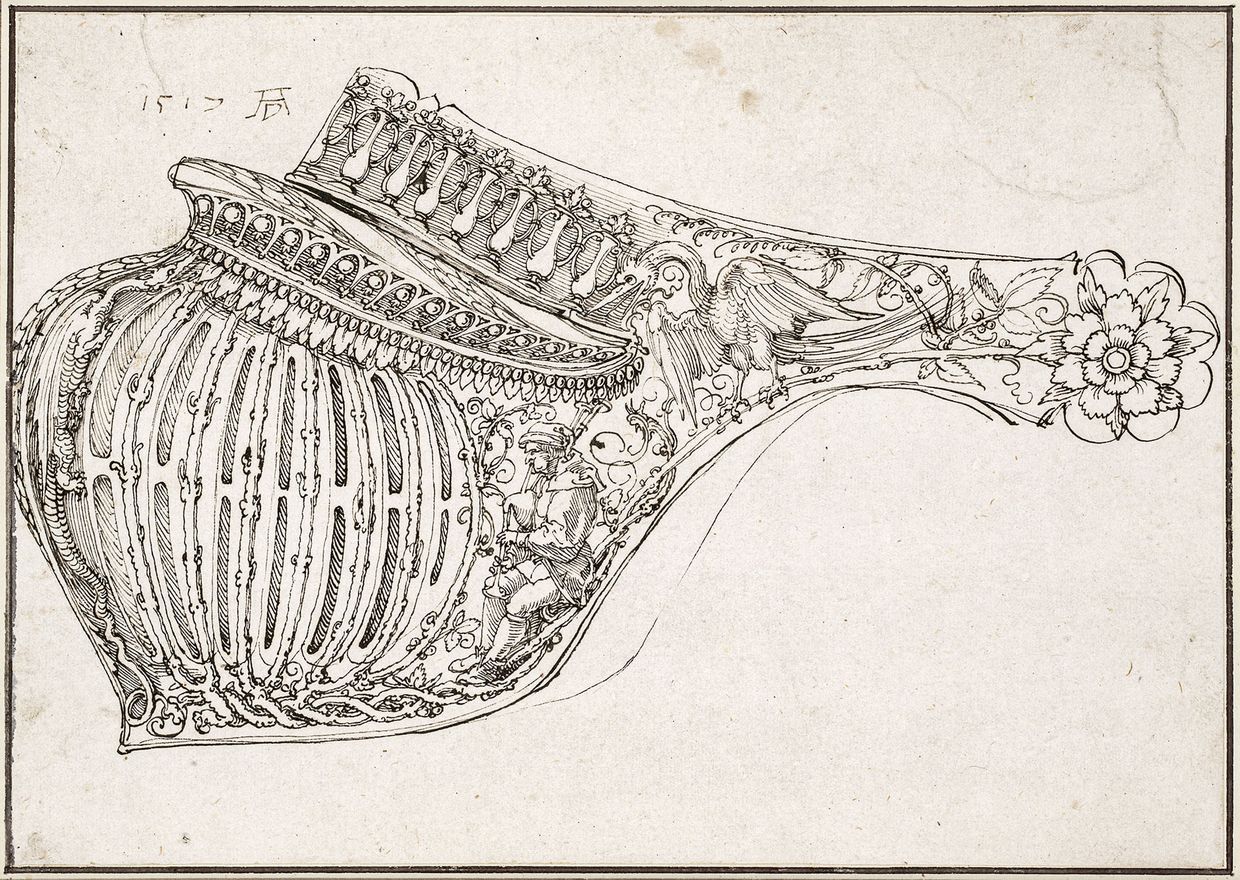

Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

1517 (?)

Paper, brown pen

193 × 275 mm

Vienna, Albertina, inv. 3151

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

1622/24

115.5 × 104 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery, inv. 490

Etching was the most important technique used to decorate armour in the Renaissance.

The artist covered the iron plate with an acid-resistant ground. He then scratched off the ground to reveal the plate. Next the plate was dipped in the mordant, allowing the acid to ‘bite’ into the uncovered areas of the plate.

Once the drawing had the required depth and strength, the artist cleaned the plate. The incisions could then be blacked or gilt.

Etching was first used to decorate arms in the High Middle Ages. In the Renaissance, artists applied this technique to printmaking.

The quality and price of armour differed widely, from cheap mass-produced munition armour to luxurious bespoke harnesses.

Many armourers produced thousands of identical breast- and backplates for foot soldiers. But famous master-craftsmen like Lorenz Helmschmid (c.1445–1516) and Filippo Negroli (c.1510–1579) created unique artworks.

An armourer commissioned to produce a made-to-measure harness was faced with a problem: the harness had to fit its wearer like a glove. But he often lived far away. As often as not it was almost impossible to take his measurements.

Armourers frequently used the future wearer’s doublet and hose to gauge his size. Or they made paper cut-outs that the client could place against his body. And for the most important clients like kings and emperors, armourers might even travel across Europe to measure a royal paunch or a pair of princely legs.

In 1526, Emperor Charles V (1500–1558) ordered a harness from Kolman Helmschmid, his armourer in Augsburg. He wanted to make sure the harness fitted him like a glove.

So he had a wax cast of his legs made at Toledo in Spain, which served as the template for a lead model. This exact cast of his legs was then dispatched to Augsburg.

At Augsburg, Helmschmid used the lead cast as his template to produce grieves and cuisses that fitted the emperor perfectly.

Sometimes, however, a bespoke harness did not fit despite the armourer’s best efforts.

Then all a customer could do was complain – something Albert, Duke of Prussia (1490–1568) did in 1531. From Königsberg in Prussia, Albert wrote to the armourer Kolman Helmschmid in Augsburg:

‘We ask you to alter the harness you made for us, which does not fit us.’

Over and under – what do I wear with my harness?

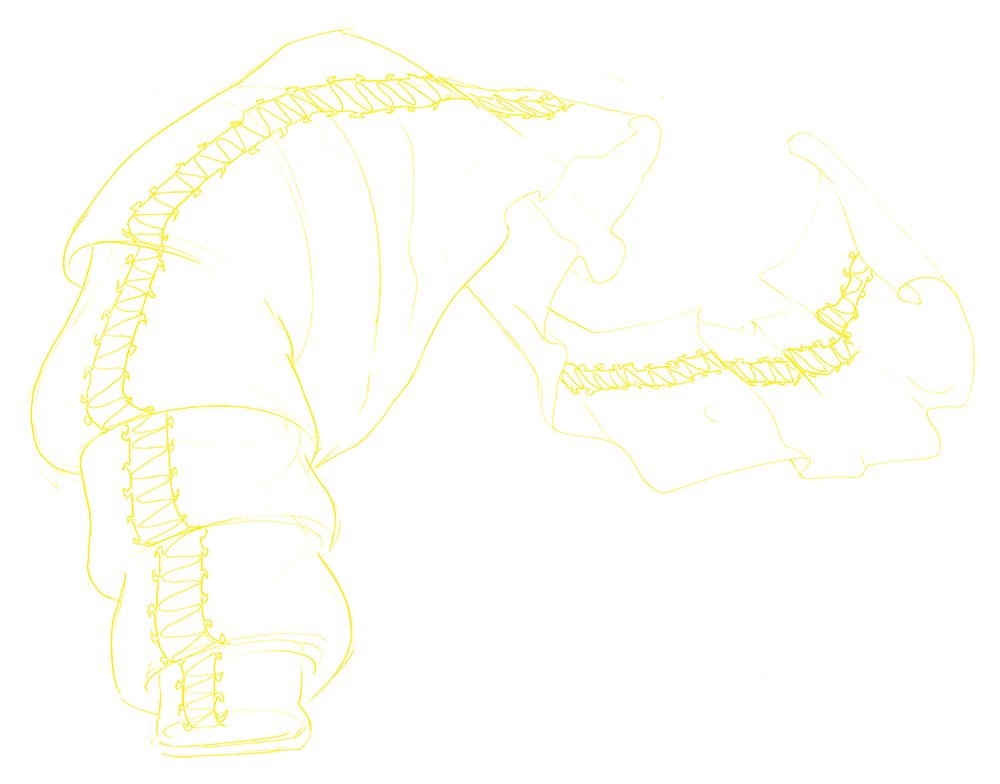

In the Renaissance, a knight in shining armour also wore other garments under and over his harness.

Those worn over his harness were costly and for display.

They were made of expensive fabrics, often emblazoned with the wearer’s coat of arms, and they emphasised his elite status.

Those worn under the harness were functional and offered additional protection.

They were made of simple materials, prevented chaffing, and alleviated the effects of heat, cold and wet conditions.

Southern German, 1560/70

Linen, gold brocade, silk, brocade, velvet, gold-wrapped thread, silk lining

H 70 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Imperial Armoury, invs. A 833n, A 833o

Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640)

c.1618

Panel

140.5 × 101.5 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery, inv. 700

Over his harness, a knight might wear a surcoat.

It was emblazoned with his arms and other symbols but also protected him from too much sun or rain.

Accessories, too, enhanced the appearance of an armoured knight. He frequently wore a gold necklace or collar, maybe one that identified him as a member of an order of chivalry. The sword worn on his left was often elaborately decorated.

His helmet was embellished with gold appliques. For a tournament he added a fantastic crest.

Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

1498

Brown pen, watercolour

408 × 324 mm

Vienna, Albertina, inv. 3067

A crest is a sculpted helmet decoration.

Crests were attached using the holes we find in the crowns of many extant helmets.

Originally, a crest functioned as a heraldic symbol. It identified the wearer. But in late-mediaeval tournaments crests mainly served as fantastic, symbolic and spectacular helmet décor.

The motifs chosen for crests often referenced the wearer’s valour and strength. Others celebrated courtly love. But many were merely witty and humourous, intended to catch the spectators’ eye.

Crests like this sun were made of painted and gilt wood or papier mâché.

Antlers featured in many crests. We know of crests with the antlers of stags, deer, chamois, rams, elks or even buffalos.

This crest depicts a fig sign (manus fica), an obscene gesture perhaps comparable to giving someone the finger. It was a symbol of the Passion of Jesus, but in the lists it was probably also used as an expletive.

This crest features a gold crown with an owl. The owl can symbolize many different things. One of them is the Passion of Christ.

The lion is one of the most popular heraldic animals. It symbolized strength, authority and a claim to power.

Together with the lion, the eagle is the most popular heraldic beast. The black eagle on a golden background was the heraldic animal of the Holy Roman Empire.

This crest depicts the Wheel of Fortune. Fortuna is the Roman goddess of fortune and the personification of luck; she spins the wheel at random, changing the positions of those on the wheel. Some suffer misfortunes, others gain windfalls regardless of whether they are peasants or kings. The crowned ‘M’ refers to Emperor Maximilian (1459–1519).

A heart pierced by an arrow was already a symbol of lovesickness in the Middle Ages. We know of many motifs relating to love that were used in mediaeval tournaments.

Bildausschnitte aus Freydal, Turnierbuch Kaiser Maximilians I.

Fashion in steel

A bespoke Renaissance harness is a formal piece of clothing for self-display.

It protected the human body from injuries but was also designed to be beautiful and fashionable.

A harness documented the wearer’s power and authority – or at least his claims to them.

But armour also reflects the aesthetic tastes of the period and culture in which it was produced.

For example, the slimline proportions of southern-German harnesses produced around 1480/90 are graceful and elegant. English harnesses from 1570/80, however, are much plumper and have wide hips.

Francesco Terzio (c.1523–1591)

c.1550

Canvas

135 × 130 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery, inv. 8063

Jörg Seusenhofer (c.1510–1580)

Innsbruck, 1547

Iron, embossed, etched, fire-gilt; brass, engraved; leather; silk velvet, silk, wool

H 177 cm, W 74.5 cm, D 69 cm; 21.85 kg

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Imperial Armoury, inv. A 638

In the Renaissance, the aesthetics of armour – its steeliness, its carapace-like concept – greatly influenced contemporary male fashion.

In 1579, Lucas van Valckenborch portrayed Archduke (later Emperor) Matthias (1557–1619) twice. In both portraits Matthias wears tight, colourful hose, blue in one painting, red in the other. With one he wears a gilt breastplate, with the other a textile doublet of a similar carapace-like style.

Lucas I. van Valckenborch (1535–1597)

1579 dated

Canvas

198 × 98 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery, inv. 6437

Lucas I. van Valckenborch (1535–1597)

1579 dated

Canvas

191 × 106 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery, inv. 4390

Such stiffened doublets were even produced in steel.

A breastplate made around 1575 for Don Juan de Austria (1547–1578) is decorated with a button border. It imitates a contemporary textile doublet. But this button border is purely ornamental.

Milan, c.1575

Iron, embossed, blued, damascened, etched, engraved, fire-gilt; brass

H 46 cm, W 40 cm, D 21 cm; 3.7 kg

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Imperial Armoury, inv. A 1049

French, c.1640

Steel

Circumference of the waist: 56.7 cm; 1.54 kg

London, The Wallace Collection, inv. A 230

Steel stays – fashion in steel for women

A number of Renaissance steel stays have come down to us. They were all clearly made for women but their use is still debated. They may have served both medical and fashionable purposes.

In 1575, the French army surgeon Ambroise Paré (c.1510–1590) described metal corsets then believed to correct or prevent the malposition of the spine.

But some women also used stays and iron plates to enhance their waistline. We have archival records of Margaret of Valois, a daughter of King Henry II of France (1553–1615), doing this.

The power of fashion to influence armour is best seen in base armour (steel skirt).

In the early sixteenth century, fashionable gentlemen wore long, pleated skirts, especially in southern Germany. Only very few harnesses with steel imitations of such textile skirts have survived.

In 1512, Emperor Maximilian I commissioned a harness for his grandson, the then twelve-year-old Archduke (later Emperor) Charles V. The cut-outs on the front and back of the skirt made it easier to walk in the harness.

Konrad Seusenhofer (gest. 1517)

Innsbruck; goldsmith work: Augsburg, 1512/13

Iron, embossed, etched, fire-gilt; silver, fire-gilt, pierced, engraved; brass

H 149 cm, W 70 cm, D 55 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Imperial Armoury, inv. A 109

Attributed to Konrad Seusenhofer (d. 1517)

Innsbruck, 1510/15

Iron, wrought, embossed, etched, fire-gilt; leather

H 51.1 cm, W 86.8 cm, T 59.7 cm; 5.84 kg

Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of William H Riggs, 1913 (14.25.790a, b)

Puffed and slashed – landsknecht fashion

In the Renaissance, landsknechts were mercenary troops from southern Germany. Their prominent role in contemporary warfare gave them privileges expressed in the clothes they sported.

The clothes favoured by landknechts were often extravagant – colourful, puffed, flared, and slashed. Their striking appearance even informed the clothes worn by members of the elite.

Some armourers imitated elements of landsknecht fashion in steel. They produced harnesses that appear to be slashed. Some have puffed sleeves that play with the illusion that they are made not of hard metal but of some soft, pliable textile.

Kolman Helmschmid (1471–1532)

Augsburg, dated 1523

Iron, wrought, embossed, etched, black-etched; leather; brass

H 140 cm, W 95 cm, D 40 cm; 19 kg

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Imperial Armoury, inv. A 374

Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472–1553), workshop

c.1526

Lime panel

125 × 82 cm

Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Rüstkammer, inv. H 0075

‘I feel a strong desire for such patterns. It is our desire that you make for us such a harness in this shape. I am prepared to pay well for it.’

Albert, Duke of Brandenburg-Ansbach (1490–1568) in a letter to Kolman Helmschmid (1471–1532), his armourer in Augsburg.

Harness as disguise

A harness was a disguise. By donning it, its wearer also assumed a role. Armour signalled desirable virtues – valour, strength, courage.

loading

Hans Seusenhofer (1470–1555),

Leonhard Meurl (d. 1547)

Innsbruck, 1526/29

Steel, wrought, embossed, etched, fire-gilt; brass, fire-gilt; leather

H 33 cm, W 23 cm, D 38 cm; 4 kg

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna,

Imperial Armoury, inv. A 461

Many tournaments were held during Carnival. Armour worn at such events often also functioned as a fanciful disguise.

Armourers produced helmets with fantastic visors in the shape of human or animal faces, or mythological grimaces. These works document both their creativity and their virtuosity.

When they were devised in the Renaissance these helmets were surely meant to elicit the reaction they still evoke today – we find them playful, weird and wonderful.

In the lists, jousters often sported female accessories such as headdresses or a bridal veil. They functioned as symbolic references to love or a particular dynastic alliance.

Attributed to Hans Seusenhofer (1470–1555)

Innsbruck, 1515/20

Steel, wrought, embossed, etched; brass

H 23.5 cm, W 25.4 cm, D 31.8 cm

Collection of Ronald S. Lauder, Promised Gift to The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Augsburg (?), c.1530

Steel, wrought, embossed, etched; brass

H 25.9 cm, W 22.9 cm, D 36.5 cm; 2.89 kg

Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bashford Dean Memorial Collection, Bequest of Bashford Dean, 1928 (29.150.3a)

‘A complete armour... including a helmet shaped like the head of a griffin’

description of the helmet made for Albert, Duke of Prussia (fig.), inventory of the collection of Archduke Ferdinand II compiled in 1596

Northern German (Brunswick?), c.1526

Steel, wrought, embossed, engraved, painted; brass

H 27 cm, W 25.5 cm, D 32.7 cm; 2.7 kg

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Imperial Armoury, inv. A 78

Alla turca

In the fifteenth and sixteenth century, the Ottomans expanded their empire to include large tracts of the Middle East, Asia, North Africa, and Europe. This is why Europeans found them rather terrifying. But their power and culture also elicited respect and interest.

European princes collected and exchanged Turkish arms. Armourers produced Turkish-inspired harnesses and weapons. Turkish and Turkish-inspired objects were also highly-esteemed gifts.

Italian, c.1540

Iron, wrought, engraved, gilt

H 23 cm, W 28 cm; 2.28 kg

Madrid, Colecciones Reales, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, inv. M 9

Ottoman, 2nd half of the 16th century

Linen, velvet velour

H 43.5 cm, dia. 28 cm

Ambras Castle Innsbruck, inv. WA 2818

in: Freydal, Tournament Book of Emperor Maximilian I

Southern German-Austrian, 1512/15

Gouache with gold and silver highlights on paper

26.5 × 38.5 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Kunstkammer (Imperial Armoury), inv. KK 5073, fol. 172

Alla turca arms and armour played a role, too, at fancy-dress parties held at court. But they were also used to arm troops that for tactical reasons needed equipment similar to that of their Ottoman enemies.

All’antica

The Renaissance witnessed a revival of interest in ancient Greece and Rome. This is reflected in contemporary all’antica – classicizing - harnesses.

This fashion was presumably born of Italy’s fascination with ancient Roman triumphs. Requests for depictions of these literary feasts fired up artists’ imagination.

In the sixteenth century, all’antica harnesses were very much en vogue. By donning such an extravagant harness, the wearer transformed himself into an ancient hero. The artists who produced these masterpieces were celebrated, highly-paid specialists.

Filippo Negroli (c.1510–1579)

Milan, 1550/55

Iron, embossed, chiseled, blackened, blued, with gold and silver damascening

H 40 cm, W 20 cm, D 38 cm; 3.35 kg

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Imperial Armoury, inv. A 693d

Bartholomäus Spranger (1546–1611)

c.1591

Canvas

163 × 117 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery, inv. 1133

In mediaeval art, old-fashioned harnesses were used to identify biblical or classical protagonists. In the Renaissance, armourers began to produce harnesses modelled on ancient armour.

Princes and generals wore these sculpted harnesses to pageants and other courtly festivities. By donning a helmet with lion-visor or a muscle cuirass, the wearer transformed himself into a modern Hercules or Caesar.

Milan, 1547–1550

Iron, embossed, blackened, fire-gilt, fire-silvered, painted; brass; leather; textile

H 180 cm (mannequin)

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Imperial Armoury, inv. A 783

Bartolomeo Campi (c.1520–1573)

Pesaro, 1546 dated

Iron, forged, blackened, gilt gold and silver damascened; brass, gilt

22.17 kg

Madrid, Colecciones Reales, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, A 188

From circa 1550, all’antica fashion changed: now classicizing harnesses were no longer fashionable.

instead, armourers began to decorate contemporary harnesses with classical motifs. They illustrated, for example, the heroic exploits of Hercules or grotesque ornaments in highly-detailed repoussé work or gold and silver inlays.

Female characters from classical mythology were also depicted in all’antica harnesses. Rembrandt, for instance, shows us Bellona, the Roman goddess of war (Lat: bellum = war), wearing such a harness. Note the head of Medusa on her shield. Her helmet is shaped like an ancient mythological creature.

Filippo Negroli (c.1510–1579), Giovan Battista Negroli (c.1517–1582)

Milan, 1550/55

Iron, embossed, chiselled, blackened, blued, gold and silver damascening

D 13 cm, diam. 61.3 cm; 4.2 kg

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Imperial Armoury, inv. A 693a

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669)

1633

Canvas

127 × 97.5 cm

Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Friedsam Collection, Bequest of Michael Friedsam, 1931 (32.100.23)

Harnesses are among the most fascinating historical and art-historical artefacts. But today they are often misunderstood. With Iron Men I hope to show new, often surprising aspects of this subject.

The exhibition brings together some of the most spectacular harnesses from the world’s leading collections.

I hope you will enjoy your visit to Iron Men, and I hope the show inspires you to explore our shared culture and history.’

Stefan Krause, Ronald S. Lauder Director Imperial Treasury, Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

Lectures further to the exhibition

The Martial Maid: Women in the Age of Armour

Chassica Kirchhoff, Detroit Inst. of Arts

Der geharnischte Mann der Renaissance – modisch gekleidet

Stefan Krause

Ottoman Impressions – Turkish-style Arms & Armour in Renaissance Europe

P. Terjanian